Introduction

In 2011, I was in graduate school in Boston pursuing a master’s degree. Although the schoolwork was what I expected, something disruptive was happening around me that felt strangely foreign. It wasn’t that I was in a completely new place, I had grown up thirty miles west of the city, but the profound change I was witnessing was as startling as if I had been shipped to another continent with a foreign language to learn. I had grown up in an upper-middle class town and I was the first in my immediate family to attend a four-year college. Those I grew up around were regular people who had little interaction with the academic theories popular in university circles. Although my undergraduate studies had brought me in contact with some new ideas, the basic assumptions about morality and truth were largely uniform in my environment. Up until that point, I had assumed a general continuity of moral thinking that spanned across generations. In many ways, my view of the world was not dramatically different than that of my grandfather, who was born in 1930.

If my experience coming of age was linked to traditional values, the world I inhabited in Boston that year marked a profound disruption in my sense of morality. It was not that my values were significantly changing, but the people I was surrounded by operated by a set of assumptions that I had simply never heard before. At the university, I saw bathrooms for the first time that were purposely gender neutral. In my classes, I was repeatedly introduced to the idea that gender did not necessarily corelate to sex assigned at birth, and I was shocked to learn that race was simply a social construct. While I had known quite a few homosexuals over the years, I had never witnessed men and women operating with a fluid sexuality that led to what I considered a bizarre mixture of both homosexual and heterosexual relationships. Something was different in Boston that had not yet made its way to the suburbs in the western part of the state. I couldn’t name it at the time, but critical theory was starting to become mainstream.

The Issue of the Day

If the political pundits are right, critical theory is the culture war issue of our time. Depending on who you ask, it is one of two things: a dangerous set of Marxist-inspired ideas that pose a serious risk to Western society, or a set of assumptions that hold the key to unlocking freedom for society’s minority groups. Fortunately, in recent years, several scholars have interacted with critical ideas in a way that has helped non-academics better understand what all the fuss is about. Even though critical theory is rarely defined by those debating its value, the ideas cultivated through critical theorists are at the heart of many current debates. From the police brutality cases that invoked wide-scale destructive protests in 2020, to the modern confusion over identity and gender, critical theory is an ideology that demands society’s attention. Thankfully, a new work has delved deep into its historical roots to help make sense of what our society is grappling to understand.

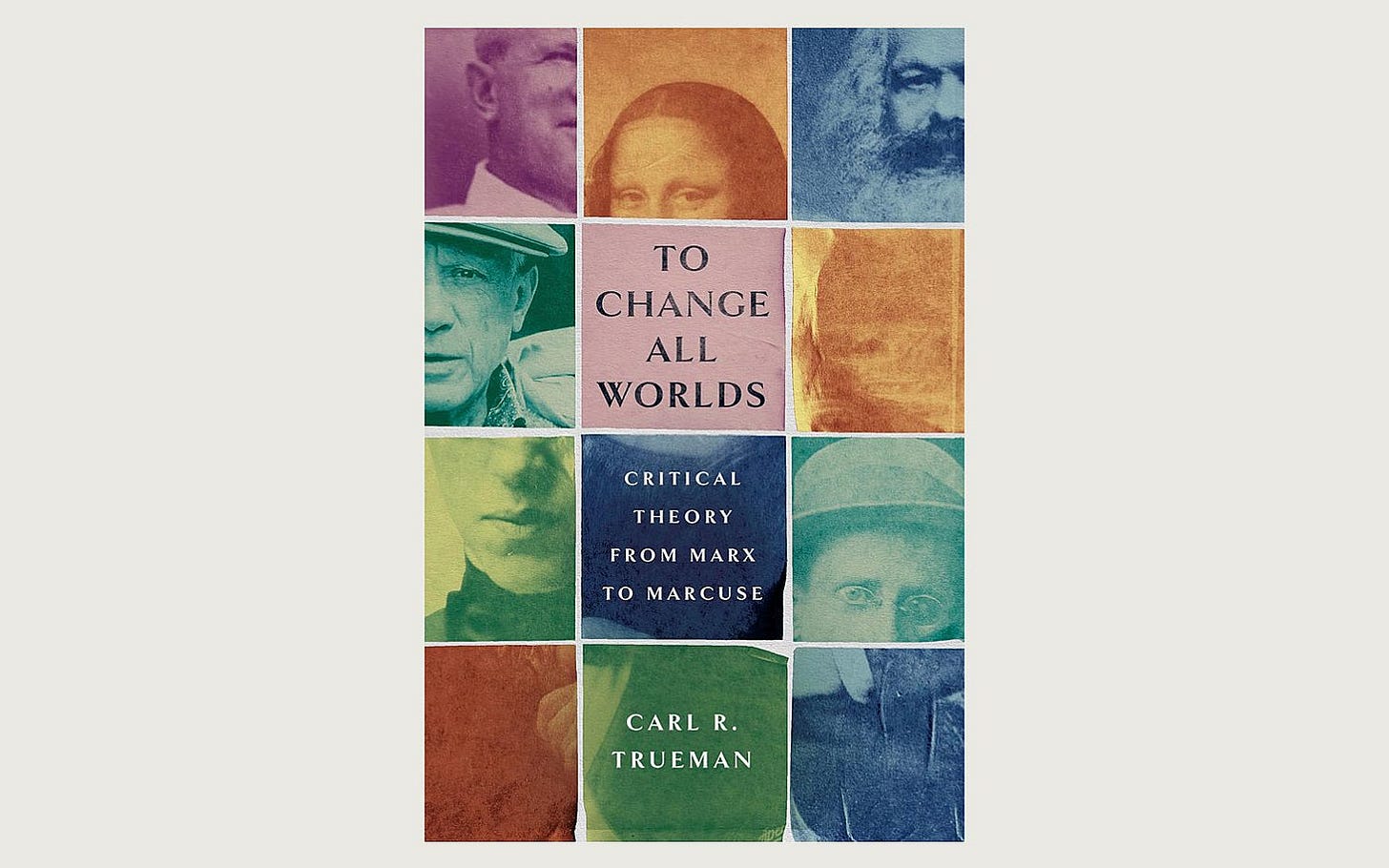

In his latest work of intellectual history, Christian historian Carl Trueman takes readers through a tour-de-force of critical theory’s historical roots. While Trueman ultimately rejects the possibility that critical theory is a helpful tool, it is clear from his interaction with thinkers across a significant time- period that he has given serious attention to its ideas. Ultimately, Trueman spends most of his time in this work focusing on the Frankfurt School that came to prominence in Germany during the 1920’s. Figures such as Wilhem Reich, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor Adorno stood at the helm of Frankfurt’s intellectual attempt to make sense of the major ideologies developing during that period. According to Trueman, a clear line in the development of critical theory can be traced from G.W.F. Hegel to Karl Marx culminating in the Frankfurt School. While critical theory has continued to develop over the years, particularly with the work on sexuality by Judith Butler and Kimberlee Crenshaw’s work on race, the Frankfurt School is clearly the ideological framework where the many iterations of critical theory was born.

A Disruptive Ideology

In many ways, the Frankfurt School must be understood within its context. In a period between WWI and WWII that witnessed the rise of disruptive ideologies like Fascism and Communism, the German thinkers associated with the University in Frankfurt were interested in the question of human liberation. Despite the rise of Hitler and Stalin during their time of active work, these intellectuals saw a path forward for humanity that rejected Nazi ideology while taking the thought of Marx many steps forward. In sum, their thinking rested on a notion of overthrowing current traditional systems to achieve economic, sexual, and psychological freedom. By focusing his work largely on Marx and Frankfurt School intellectuals, Trueman argues that critical theory is a revolutionary ideology whose aim is to throw off any traditional values to achieve its goal: changing all worlds.

The goal of changing all world’s rests on some key ideas developed through the Frankfurt School. The first idea is that of alienation. The concept of alienation is not uniquely Marxist but was defined by Karl Marx as a process where working class citizens are transformed from people into objects. According to Marx, capitalist society functions in a way where humans are progressively estranged from their work, their own human nature, and even themselves. While the theory is complex, Marx is particularly concerned with how capitalism alienates workers from the fruit of their labor. Instead of enjoying the result of their work, they are engulfed in a system that swallows up their labor and their humanity for a paycheck from the ruling class. It is in this part of the book that Trueman shines brightest.

The theory of alienation is a bedrock of critical theory, but it cannot stand by itself. To support the concept of alienation, the critical theorists also claimed that humanity was subject to a false consciousness of sorts. According to Trueman, the “whole point of false consciousness is that the ideas which it embodies do not serve the interests of those who hold them” (40). For example, the factory worker is harmed by his belief in private property because it leads to his poverty and alienation. According to critical theorists, the belief systems that make up a collective false consciousness are created by the ruling class to subject the working class. These two bedrock ideas are foundation to critical theories development. For race to be a social construct and gender to be fluid, the traditional notions of morality must be challenged. What better way to challenge traditional assumptions of truth than to argue that the collected masses are delusional? For the critical theorists, things are never really as they appear. As Trueman wisely notes, debating the critical theorists on these points is futile. Their concept of false consciousness serves as a diversion for almost any critique made against the ideology.

A Step Too Far?

The key themes and ideas of critical theory are largely incongruent to Christianity, as Trueman notes. Critical theory is mainly concerned with its end goal of throwing off traditional terms to achieve human liberation. For the Christian, this liberation cannot be found in human systems and can only be achieved in Christ. Although Christians are wise to be suspect of critical thought, I wonder if Trueman goes too far in his assessment of the ideology. Because of critical theory’s revolutionary nature, Trueman does not see critical theory as a valuable tool to help Christians think through social engagement. While it would take some wisdom in discerning which critiques of modern society Christians should accept, it seems as though at least some of the Frankfurt school’s critiques are valid. Perhaps some of the critiques against capitalism as an alienating force are valid? Maybe our society does suffer from a type of false consciousness where much of our thinking is outsourced to “professionals” rather than the wisdom of tradition and Scripture. If this is true, why can’t Christians respond to these problems with solutions that improve rather than tear down? Although Trueman is correct in that critical theory’s ambition is not to correct abuses but to overthrow the system, I struggle to understand why Christians cannot separate the critiques from the prescriptions.

To Change All Worlds succeeds in its goal to articulate the history of critical theory. Trueman, after all, is an intellectual historian that focuses his work mainly on how ideas develop over time. For anyone who has read The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, Trueman’s ability to trace thought across continents, individuals, and time periods must be recognized as impressive. Trueman does a wonderful job in this book articulating the main ideas that create the foundation of critical theory. While some recent scholars have undertaken the work of identifying the root of critical theory much earlier, particularly in Watkins book on Biblical critical theory, Trueman has done the church and society a favor by making early and mid-century European intellectuals accessible in our day.

While the book is a helpful addition to understanding critical theory, I was left wishing that Trueman would have gone a step further. This desire was particularly felt when Trueman spoke directly to the church towards the end of the book. In Trueman’s “Christian Response,” his argument is that all of the “central challenges to human existence” identified by the critical theorists are “resolved in Christ” (226). For example, while critical theory sees humanity as alienated from their true selves by an oppressive web of assumptions, Christ reconciles us together in Christ. Where critical theory creates categories that divide people, the Bible declares that in Christ there is no Jew or Gentile, slave or free. Finally, Trueman sees the Gospel as dealing with the problem of alienation. In Christ, Trueman notes, human beings are subjects of Christ while also remaining free in Christ. The Gospel, rather than a new social construct, is what restores humanity through reconciliation in Christ.

While I applaud the biblical truth Trueman explains in this book, it fails to consider that even Christians are harmed by dysfunctional systems. Someone can be reconciled to Christ and be part of a healthy church while also suffering from the dysfunction of our society. An example would be the Christian who is a victim of crime. It would be unthinkable to tell a victim of theft that their only solution was Christ. In addition, if there was a social system that was making theft more likely, that person would also want socity improved. Similarly, those who are manipulated by slick marketing campaigns to spend their money on things they do not need deserve serious intellectuals that will push back against some of capitalism’s excesses. While Trueman pushes back against separating the critiques of critical theory from its prescriptions to society, I think a better option would be evaluating each critique on its own merit. In this case, I think Christians would find some the work done by critical scholars helpful.

Thanks for reading Church and State! If you like what you are reading, please consider supporting my work in two ways: First, hit the SUBSCRIBE button to receive my newsletter. In addition, please consider sharing my work with someone who may find it interesting. Thanks!